After celebrating the dads in your life on Father’s Day, consider raising a glass to Charles Babbage, the 19th-century Englishman known as the “Father of Computing.” An independently wealthy man, Babbage was able to indulge in his fascination in mathematics and science to the world’s benefit. His impact can be found not only in actual inventions, but also in prescient plans, such as the concept of a “black box” to derive information about railway accidents.

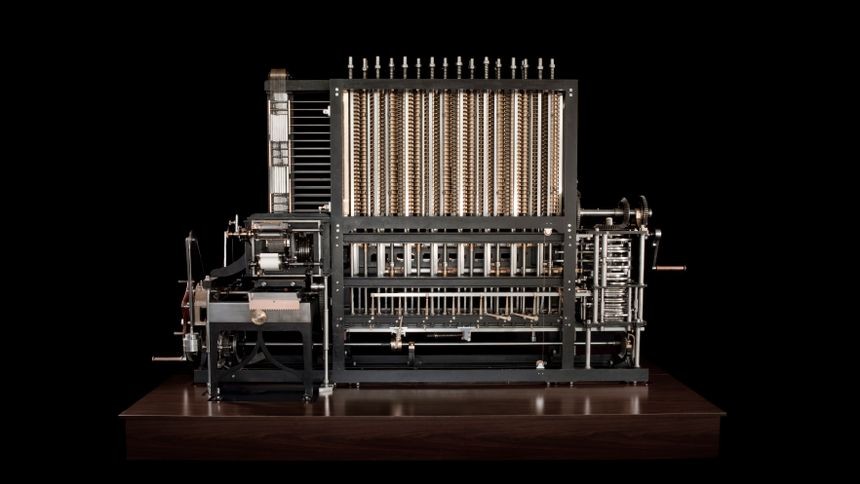

He is most known for another invention that he didn’t actually construct: the Analytical Engine, aka Difference Engine No. 2, which was finally completed in London in 2002 according to original drawings. The design was a follow-up to Difference Engine No. 1, which Babbage invented in 1821. One example of the Difference Engine can be found at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. By manipulating a set of disks and cranks, a user can perform a mathematical calculation using the device

His legacy lives on

In 1832, Babbage began working to take his design several steps farther. His vision for the Difference Engine No. 2 was a machine that could be programmed to follow instructions—which would have made it the first computer. He built fragments of the machine and demonstrated its potential as a parlor trick for guests including Charles Darwin and Charles Dickens. Although he did not fully build this “analytical engine,” he wrote copiously about his plans, as did his friend Ada Lovelace.

After his death in 1871, his papers ended up at the Science Museum in London, where staff began building Difference Engine No. 2 in 1991. The fully realized Analytical Engine, complete with a printing mechanism, weighs in at more than 5 tons and contains more than 8,000 parts.